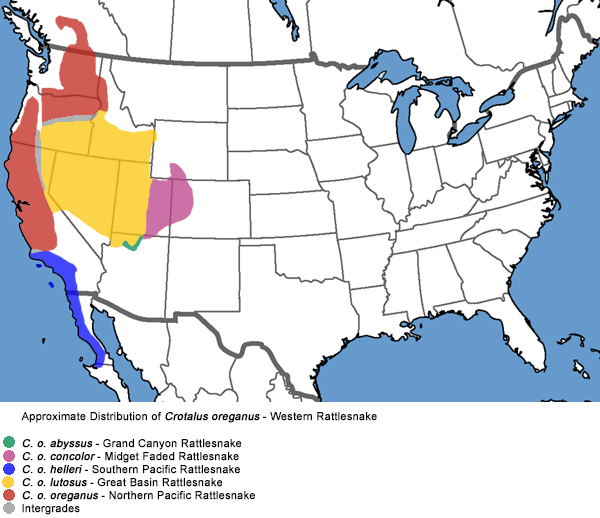

Western Rattlesnake - Crotalus oreganus

Southern Pacific Rattlesnake - Crotalus oreganus helleri

Meek, 1905(= Crotalus helleri; = Crotalus viridis helleri)

Description • Taxonomy • Species Description • Scientific Name • Alt. Names • Similar Herps • References • Conservation Status

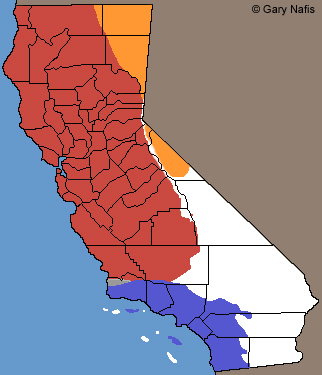

Dark Blue: Range of this subspecies in California

Crotalus oreganus helleri - Southern Pacific Rattlesnake

Range of other subspecies in California:

Orange: Crotalus oreganus lutosus -

Great Basin Rattlesnake

Red: Crotalus oreganus oreganus -

Northern Pacific Rattlesnake

Gray: Intergrade Range

Click on the map for a topographical view

Map with California County Names

Venomous and Potentially Dangerous! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Adults |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, San Diego County © Howard Lange | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, San Diego County | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, San Diego County | Adult, San Diego County © Bruce Edley |

Captive adult, courtesy of the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Ventura County © Patrick Briggs |

Adult, Ventura County © Patrick Briggs |

Adult, Ventura County © Patrick Briggs |

Adult, San Diego County © Chris Gruenwald |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Santa Catalina Island, Los Angeles County © Nathan Smith |

Adult, Santa Catalina Island, Los Angeles County © Nathan Smith |

Adult, San Diego County © 2003 Chris Gruenwald |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Los Angeles County © Koby Poulton |

Adult, near La Jolla, San Diego County, about 1/3 mile from the beach. | Adult, Riverside County © Michael Clarkson |

Snakes of two different color variations found in the same location in San Diego County. © Steve Bledsoe | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Los Angeles County © Gregory Litiatco | Dark adult, San Bernardino County © Jeff Ahrens |

Adult found on a doorstep in Orange County. © Jay Selman | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Very dark adult, Cuyamaca Mountains, San Diego County © Stuart Young | Adult, Santa Barbara County, with unusual brown coloring and a gold pattern. © Brian Hinds | Adult, Ventura County © Wayne Darrell Crank Jr. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adults, Santa Barbara County © Ryan Sikola |

Adult with long string of rattles, 4000 ft. San Diego County mountains © James R. McFadden |

Adult, San Diego County © Paul Maier |

High-elevation black adult with some blue coloring on some of the lower scales, San Bernardino County © John Buckman |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, San Diego County © Noah Correia This rattlesnake is in a defensive position, head back, ready to strike, rattling its tail, and puffing itself up to look bigger and more threatening. Click on the picture on the right to see an animated example of the snake getting a little bit larger. |

Adult, San Diego County © Noah Correia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult in defensive pose, Orange County © Brian Nann |

Adult in defensive pose, Orange County © Brian Nann |

Adult with brownish-green coloration (resembling the coloration of a Mojave Green Rattlesnake) found in the Santa Monica Mountains, Ventura County © Max Roberts |

Yellowish adult, Orange County © Max Roberts |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Large black adult, Los Angeles County © Eric DeLeon | Adult, Los Angeles County © Zeev Nitzan Ginsburg |

Adult, San Diego County © Marcus Rehrnam |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, eastern San Diego County © Nick Jones | Adult, Orange County © Mark Baskin | Adult, Orange County © Mark Baskin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult found underneath a discarded microwave oven in Riverside County © Zeev Nitzan Ginsburg |

Adult, Santa Catalina Island, Los Angeles County © Matthias Lemm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This adult was crossing a sandy road one morning at the eastern edge of San Diego County. It was surprised to see me and made a quick U-turn then crawled into a bush, leaving me a good look at the tracks it made in the sand. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Juveniles |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Juvenile with yellow tail, Los Angeles County (Note that the rattle consists of only one segment which does not produce a sound.) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Juvenile, Santa Monica Mountains, Los Angeles County © Colin Byrne |

Juvenile, about 12 inches in length, Orange County, flattening its body to appear larger. © David Fong |

Juvenile with U.S. quarter-dollar coin |

Juvenile, San Bernardino County © Patrick Briggs |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tiny juvenile in March (next to house keys for size reference), coastal Riverside County © Brett Badeaux |

Pale juvenile, San Bernardino County © Wayne Darrell Crank Jr. |

Juvenile, San Diego County |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dark neonate, Orange County © Nozomi |

Juvenile, San Diego County © Verle Thompson |

Juvenile, Los Angeles County © Zeev Nitzan Ginsburg |

Juvenile basking on loose bark, Ventura County © Mark Kroenke | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Orange county juvenile on a ledge with a very nice view. © Mark Baskin | Juvenile, Los Angeles County © Eric DeLeon |

Juvenile full from recent meal, San Bernardino County © Jeff Ahrens |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tails and Rattles |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult tail and rattle | Adult tail and rattle, Los Angeles County

© 2006 Koby Poulton |

Adult with long rattle, San Diego County © James R. McFadden | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The tail of a newborn juvenile has only a single silent yellow button on the end of its tail. As it grows it will add rattle segments at the end of the tail behind the button, which remains at the end. | Newborn rattle button | Juvenile tail and small rattle | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Photos © Agata Labianca This adult Southern Pacific Rattlesnake observed in the Santa Monica Mountains in Los Angeles County is missing the end of its tail with the rattle. It could have been bitten off by an animal or crushed by a bicycle or automobile tire or maybe somebody cut it off. That's unlikely on a live snake, though it's not uncommon to find a dead rattlesnake with the rattle cut off. Since it's possible to find a live rattlesnake without a rattle, one should always learn how to recognize a rattlesnake by its other features besides the rattle - the pattern, the body shape, and the shape of the head. There are stories circulating that rattlesnakes are evolving and losing their rattles because they no longer use them due to the fact that it's safer for them to remain silent around humans, but here's no real proof that this is happening. Here's more information about that. |

This Los Angeles County adult rattlesnake has no rattle. It appears to have been lost in a very old injury since the stump is well healed. The snake shakes its tail as if it still has the rattle, although it seems to rely more on other threat displays like hissing and defensive postures. © Zeev Nitzan Ginsburg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Unusual or Interesting Color and Pattern Variations in Southern Pacific Rattlesnakes |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melanistic patternless adult, Riverside County. © Tony Covell |

Melanistic Adult, Ventura County © Patrick Briggs |

Melanistic adult, San Gabriel Mountains, Los Angeles County © Lori Paul. This snake had a completely dark belly. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young albino found dead on a road in Orange County. © Mike Pecora Warning - If you click on the image on the left you'll see the entire snake, but there is some blood and lots of ants. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Firefighter paramedic Chris Sperber and firefighter specialist Daniel Craig were called out to Newhall in Los Angeles County at midnight to help someone deal with a snake that was found in a bathroom next to a pool. This beautiful patternless and dark striped rattlesnake is what they found and caught. The snake was killed, following LA County Fire Department policy, which explains why the head is missing. Photos © Ray Ortiz LACoFD. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This unusual striped neonate was found in early October in coastal San Diego County. © Eric Quinn | Pale juvenile, Orange County © Steve Bledsoe | Hypomelanistic adult, San Diego County. © Bryce Anderson | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, San Bernardino Mountains, San Bernardino County © Stuart Williams. This snake is ready to shed its skin, called being "in the blue," and it actually shows some blue coloring on the head and lower sides. |

Black adult, Santa Monica Mountains, Los Angeles County © Colin Byrne. Black Southern Pacific rattlesnakes are not uncommon in southern California mountains. |

Southern Pacific Rattlesnakes that are almost entirely dark in color such as these occur around Southern California but they seem to be prevalent around Idyllwyld on Mount San Jacinto. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult hiding in pine needles, San Jacinto Mountains, Riverside County, © Douglas Brown |

Adult, near Idylwyld, San Jacinto Mountains, Riverside County © Kim Orta & Adrian Sotomayor |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult with green and pink coloring, San Diego County. © Bryce Anderson |

Intergrade with C. o. oreganus, Santa Barbara County © Benjamin German | Pale adult with bluish coloring, Los Angeles County © Kahleo Thompson | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Breeding Season Behavior |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Male "Combat Dance" |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Two adult males wrestling for dominance on March 11th in Los Angeles County (the smaller yellower one won.) © Robert Hamilton Watch a YouTube Video of these snakes. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Males doing a "Combat Dance," Ventura County © 2006 Steve Broggie |

This short video shows two males wrestling for dominance over a female snake that is probably hiding nearby during the May breeding season, in Orange County. © Paul Galvin |

A short video of a pair of male Southern Pacific Rattlesnakes wrestling over a mate in Los Angeles County. | This is a short video of a pair of male Southern Pacific Rattlesnakes doing the combat dance in San Diego County. © Tom Hardin |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Breeding Pairs | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult male and adult female mating in March in San Diego County. © Steve Bledsoe |

A pair of breeding adults, Orange County © Brian Nann |

Pair of breeding adults exactly as found underneath a board in March in San Diego County grassland. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Southern Pacific Rattlesnake Predation |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult eating a squirrel near Idyllwild, Riverside County. This snake was fortunate to live under the deck of a building inhabited by biologists who carefully tolerated its presence and watched it emerge to take advantage of squirrels that fed beneath a bird feeder © 2006 Sheri Lubin |

Juvenile eating a Great Basin Fence Lizard in San Diego County © Andrew Klotz |

This juvenile Southern Pacific Rattlesnake was observed in Los Angeles County eating a Western Side-blotched Lizard that had been killed on a trail and was dead for some time before it was found by the snake, which took advantage of a free meal. © Mark Rothenay |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult eating a rat on an Orange County hiking trail (left) and what it looks like afterwards (right) © Fred Booth |

Juvenile eating a Great Basin Fence Lizard on a residential patio in Orange County © Cliff Peebles |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Predation on Southern Pacific Rattlesnakes |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| California Kingsnakes eat snakes along with other animals. They are immune to rattlesnake venom, so they sometimes eat rattlesnakes. This one is eating a juvenile Southern Pacific Rattlesnake. © Kimberly Deutsch |

This California Kingsnake is almost finished eating a juvenile Northern Pacific Rattlesnake. © Michele Coughlin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A California Striped Racer - Coluber lateralis lateralis, eating a juvenile Southern Pacific Rattlesnake in Los Angeles County. © Anthony |

This Sierra Mountain Kingsnake is eating a juvenile Northern Pacific Rattlesnake, © Patrick Briggs |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A California Kingsnake eating a Southern Pacific Rattlesnake in Orange County © Ed Smith |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| California Kingsnake eating a Southern Pacific Rattlesnake in Los Angeles County © Chris DeGroof |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This California Kingsnake was discovered eating a juvenile Southern Pacific Rattlesnake in the Los Padres Mountains, Santa Barbara County © Benjamin Bruno |

A Red Racer eats a juvenile Southern Pacific Rattlesnake in Riverside County © Steven Elliott | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This adult Red Coachwhip was observed preying on a Southern Pacific Rattlesnake next to a basket at a disc golf park in Ventura County. © Bake Stevens | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

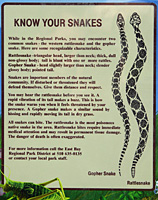

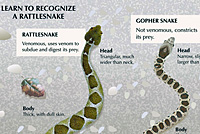

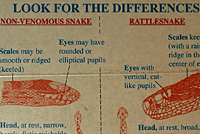

How to Tell the Difference Between Rattlesnakes and Gophersnakes |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Harmless and beneficial gophersnakes are sometimes mistaken for dangerous rattlesnakes. Gophersnakes are often killed unnecessarily because of this confusion. (It's also not necessary to kill every rattlesnake.) It is easy to avoid this mistake by learning to tell the difference between the two families of snakes. The informational signs shown above can help to educate you about these differences. (Click to enlarge). If you can't see enough detail on a snake to be sure it is not a rattlesnake or if you have any doubt that it is harmless, leave it alone. You should never handle a snake unless you are absolutely sure that it is not dangerous. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Habitat |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat, San Gabriel Mountains, Los Angeles County |

Habitat, San Diego County coastal scrub |

Habitat, Carlsbad, coastal San Diego County. (This location was bulldozed and developed a few years later.) |

Habitat, San Gabriel Mountains, Los Angeles County | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat, coastal Riverside County | Coastal San Diego County grassland habitat that is rapidly disappearing due to development. © Brian Hinds | Habitat, riparian canyon, Los Angeles County |

Den habitat, Los Angeles County © Koby Poulton |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat, Santa Monica Mountains, Los Angeles County © Colin Byrne | Habitat, Santa Monica Mountains, Los Angeles County © Colin Byrne | Habitat, Santa Ana Mountains, Riverside County |

Snake in habitat, near La Jolla, San Diego County, about 1/3 mile from the beach. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Short Video and Sounds of Southern Pacific Rattlesnakes |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A Southern Pacific Rattlesnake poses and rattles and crawls away at night in Los Angeles County. | A short video of two males wrestling for dominance over a female snake that is probably hiding nearby during the May breeding season, in Orange County. © Paul Galvin |

A pair of male Southern Pacific Rattlesnakes wrestle over a mate in Los Angeles County. | This is a short video of a pair of male Southern Pacific Rattlesnakes doing the combat dance in San Diego County. © Tom Hardin |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Listen to the rattling of a captive adult (shown above) courtesy of the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum. © Jeff Rice / Western Soundscape Archive Not to be used without permission. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

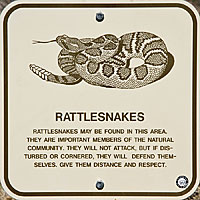

| San Diego County park warning sign. |

Sign at Santa Barbara County rest area |

Sign in San Gabriel Mountains | Click on the picture to see more rattlesnake signs. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

"Rattlesnakes are also among the most reasonable forms of dangerous wildlife: their first line of defense is to remain motionless; if you surprise them or cut off their retreat, they offer an audio warning; if you get too close, they head for cover. Venom is intended for prey so they're reluctant to bite, and 25 to 50 percent of all bites are dry - no venom is injected." |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the July 2025 State of California Special Animals List and the July 2025 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists, but they don't change a great deal from year to year.. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists: https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals. A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page. If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings. Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website. |

||

| Organization | Status Listing | Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking | ||

| NatureServe State Ranking | ||

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) | None | |

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) | None | |

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife | None | |

| Bureau of Land Management | None | |

| USDA Forest Service | None | |

| IUCN | ||

|

|

||

Return to the Top

© 2000 -