|

|

|

| Adult, Los Angeles County |

Adult, Los Angeles County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, San Luis Obispo County |

Adult, Los Angeles County |

Adult, San Luis Obispo County in defensive pose with offensive secretions visible on tail |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Los Angeles County |

Adult, San Luis Obispo County |

Adult, San Gabriel Mountains, Los Angeles County © Brad Alexander |

|

|

|

|

Adult, Santa Ana Mountains,

Orange County © Jason Jones |

Adult, San Luis Obispo County |

Adult from Idyllwild, Riverside County.

© Stuart Young |

Adults and juvenile from Idyllwild, Riverside County. © Stuart Young |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, San Diego County © Stuart Young |

Adult, Palomar Mountain, San Diego County © Stuart Young |

Pale, probably Leucistic, Adult, San Bernardino County. © Brian Hinds |

|

|

|

|

| Adult from the Santa Ana Mountains, Riverside County © Nathan Ray |

Adult from Palomar Mountain, San Diego County, found near some Large-blotched Ensatinas. © Mark Gary |

Adult, San Bernardino National Forest

© Wayne Darrell Crank Jr. |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, found farther east than expected in the Temblor range at the western edge of Kern County. © Ryan Sikola |

|

|

|

|

Adult, Santa Barbara County

© Max Roberts |

Adult from the San Jacinto Mountains in Riverside County © Max Roberts |

Adult, Monterey County

© Benjamin Genter |

The tail of an Ensatina is

constricted at the base |

| |

|

|

|

Juveniles |

|

|

|

|

| Juvenile, San Luis Obispo County |

Juvenile, San Luis Obispo County |

Adult Large-blotched Ensatina and juvenile Monterey Ensatina found under the same log on Palomar Mountain, San Diego County © Jay Keller |

| |

|

|

|

| Intergrades (or Hybrids) |

Currently, E. e. klauberi-Large-blotched Ensatina is treated as a subspecies, which makes the salamanders shown below intergrades with the related subspecies featured on this page, E. e. eschscholtzii - Monterey Ensatina. Some researchers recognize E. e. klauberi as a full species, which makes the salamanders shown below hybrids of two species - Ensatina klauberi and Ensatina eschscholtzii. For those who don't recognize Ensatina subspecies, they're just another variation in the highly-variable species.

|

|

|

|

|

Juvenile from intergrade zone,

Monterey County |

Adult from intergrade zone,

Monterey County |

Juvenile, Monterey County © Dave Feliz |

Adult from the intergrade zone with

E. e. xanthoptica - Yellow-eyed Ensatina, coastal Santa Cruz County.

© Scott Peden |

|

|

|

|

Hybrid or intergrade with E. e. klauberi, Palomar Mountain,

San Diego County © Jeff Nordland |

Hybrid or intergrade with

E. e. klauberi, San Diego County

© Brad Alexander |

Hybrid or intergrade with E. e. klauberi, Palomar Mountain, San Diego County

© Jeff Nordland |

|

|

|

|

Hybrid or intergrade with E. e. klauberi, Palomar Mountain,

San Diego County © Alex Bairstow |

Hybrid, San Diego County © Paul Maier |

Top - E. e. eschscholtzii

Middle - E.e.eschscholtzii x E.e.klauberi

Bottom - E. e. klauberi

San Diego County © Paul Maier |

|

|

|

|

Juvenile hybrid or intergrade with E. e. klauberi, about 45-50 mm long including tail,

Palomar Mountain,San Diego County © Robyn J. Waayers |

|

| |

|

|

|

| Ensatina Courtship |

|

|

|

|

| Adult pair of courting adults, Santa Barbara County © Spencer Riffle |

|

|

|

This pair of courting adults was found on a wet January night in San Diego County.

© Jeff Nordland |

This pair of courting adults was found on a wet January night in San Diego County. © Jeff Nordland |

|

|

|

|

Females With Eggs |

|

|

|

|

© Joe Garcia

On August 3rd, Joe Garcia found these Ensatinas attending their eggs under a board underneath a

house in Monterey County. Female Ensatinas stay with their eggs to protect them until they hatch. |

|

|

|

|

|

© Joe Garcia

On September 19th, Joe returned to the crawl space, looked under the board, and found that most of

the eggs of one female had just hatched, with at least 10 hatchlings still next to the eggs. |

|

|

|

|

|

© Joe Garcia

Two days later, all of the eggs of both females had hatched and the juveniles were still with the females.

Juveniles probably remain where they hatched until the first rains of the season, which could be months. |

|

| |

| Habitat |

|

|

|

|

Coastal Redwood Forest Habitat,

Monterey County

|

Habitat,

Monterey County

|

Coastal Redwood Forest Habitat,

Monterey County

|

Habitat, 3,800 ft.,

Los Angeles County |

|

|

|

|

| Habitat, San Luis Obispo County |

Habitat, San Luis Obispo County |

Habitat of Hybrids, San Diego County

© Paul Maier |

|

| |

|

|

|

| Short Video |

|

|

|

|

| A juvenile and an adult Monterey Ensatina are uncovered in the redwoods. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Description |

| |

| Size |

An adult Ensatina measures from 1.5 - 3.2 inches long (3.8 - 8.1 cm) from snout to vent, and 3 - 6 inches (7.5 - 15.5 cm) in total length.

|

| Appearance |

A medium-sized salamander.

The legs are long, and the body is relatively short, with 12 - 13 costal grooves.

Nasolabial grooves are present.

The tail is rounded and constricted at the base, which will differentiate this salamander from its neighbors.

|

| Color and Pattern |

This subspecies is reddish brown to pinkish brown above, and whitish below, with orange or reddish-orange on the base of the limbs.

The eyes are very dark with no yellow markings. |

| Male / Female Differences |

Males have longer, more slender tails than females, and a shorter snout with an enlarged upper lip, while the bodies of females are usually shorter and fatter than the bodies of males.

|

| Life History and Behavior |

A member of family Plethodontidae, the Plethodontid or Lungless Salamanders.

Plethodontid salamanders do not breathe through lungs. They conduct respiration through their skin and the tissues lining their mouth. This requires them to live in damp environments on land and to move about on the ground only during times of high humidity. (Plethodontid salamanders native to California do not inhabit streams or bodies of water but they are capable of surviving for a short time if they fall into water.)

Plethodontid salamanders are also distinguished by their nasolabial grooves, which are vertical slits between the nostrils and upper lip that are lined with glands associated with chemoreception.

All Plethodontid Salamanders native to California lay eggs in moist places on land.

The young develop in the egg and hatch directly into a tiny terrestrial salamander with the same body form as an adult.

(They do not hatch in the water and begin their lives as tiny swimming larvae breathing through gills like some other types of salamanders.)

|

| Activity |

Ensatina live in relatively cool moist places on land becoming most active on rainy or wet nights when temperatures are moderate. They stay underground during hot and dry periods where they are able to tolerate considerable dehydration. They may also continue to feed underground during the summer months.

High-altitude populations are also inactive during severe winter cold.

Adults have been observed marking and defending territories outside of the breeding season. |

| Territoriality |

| Adults have been observed marking and defending territories outside of the breeding season. |

| Longevity |

| Longevity has been estimated at up to 15 years. |

| Defense |

When it feels severely threatened by a predator, an Ensatina may detach its tail from the body to distract the predator. The tail moves back and forth on the ground to attract the predator while the Ensatina slowly crawls away to safety. The tail can be re-grown.

The tail also contains a high density of poison glands. When disturbed, an Ensatina will stand tall in a stiff-legged defensive posture with its back swayed and the tail raised up while it secretes a milky white substance from the tail, swaying from side to side. This noxious substance repels predators, although some experienced predators learn to eat all but the tail. The poison is also exuded from glands on the head.

If a person gets the poison on their lips, they will experience some numbness for several hours. (Charles Brown - Ensatina.net)

Rarely, an Ensatina may make a hissing or squeaking sound when threatened. |

| Predators |

Predators include Stellar's Jays, gartersnakes, and raccoons.

(Kuchta and Parks, Lanoo ed. - Amphibian Declines... 2005) |

| Diet and Feeding |

Ensatinas eat a wide variety of invertebrates, including worms, ants, beetles, spiders, scorpions, centipedes, millipedes, sow bugs, and snails.

They expell a relatively long sticky tongue from the mouth to capture the prey and pull it back into the mouth where it is crushed and killed, then swallowed.

Typically feeding is done using sit-and-wait ambush tactics, but sometimes Ensatinas will slowly stalk their prey. |

| Sound |

"Rarely, it may produce a squeak or snakelike hiss, quite a feat for an animal without lungs!"

(Stebbins & McGinnis 2012)

|

|

This frightened Humboldt County Ensatina is raised up in defensive mode, excreting a milky white defensive liquid on its head and tail. It jerks its head several times, and each time it makes a very faint squeaking sound.

Click the picture to play a short video to hear the squeaking. (You might need to turn the volume all the way up.)

© Cory Walker |

| Reproduction |

Reproduction is terrestrial.

Mating takes place in Fall and Spring, but may also occur throughout the winter.

Stebbins describes an elaborate Ensatina courtship involving the male rubbing his body and head against the female eventually dropping a sperm capsule onto the ground which the female picks up with her cloaca. You can watch an Ensatina courtship video on YouTube.

The female can store the sperm until she determines the time is right to fertilize her eggs.

At the end of the rainy season, typically April or May, females retreat to their aestivation site under bark, in rotting logs, or in underground animal burrows, and lay their eggs. |

| Eggs |

Females lay 3 - 25 eggs, with 9 - 16 being average.

Females remain with the eggs to guard them until they hatch.

(Pictures of Ensatinas with their eggs and hatchlings)

In labs, eggs have hatched in 113 - 177 days. |

| Young |

Young develop completely in the egg and hatch fully formed and probably leave the nesting site with the first saturating Fall rains, or, at higher elevations, after the snow melts.

|

| Habitat |

Inhabits moist shaded evergreen and deciduous forests and oak woodlands, mixed grassland, and chaparral. Found under rocks, logs, other debris, especially bark that has peeled off and fallen beside logs and trees.

Most common where there is a lot of coarse woody debris on the forest floor. In dry or very cold weather, stays inside moist logs, animal burrows, under roots, wood rat nests, under rocks.

|

| Geographical Range |

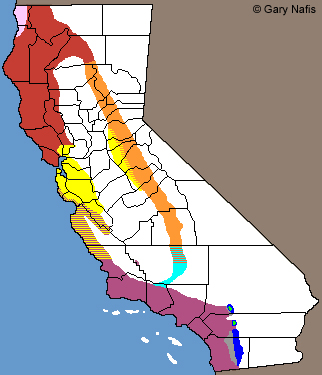

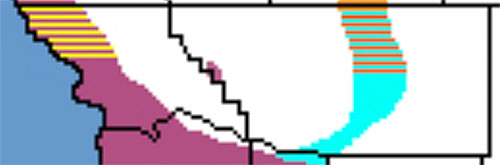

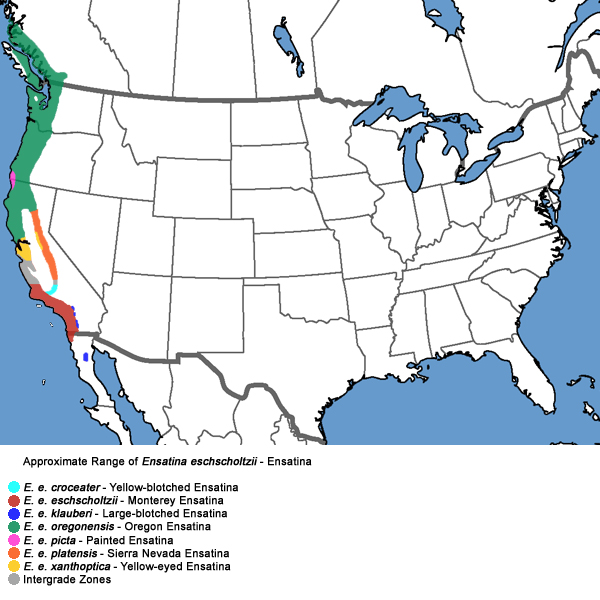

Monterey Ensatina is found in southern California and northern Baja California, from San Luis Obispo County south along the coast to the extreme northwest coast of Baja California. They are also found in the San Bernardino and San Gabriel mountains up to 6,000 ft., (1,800 m.)

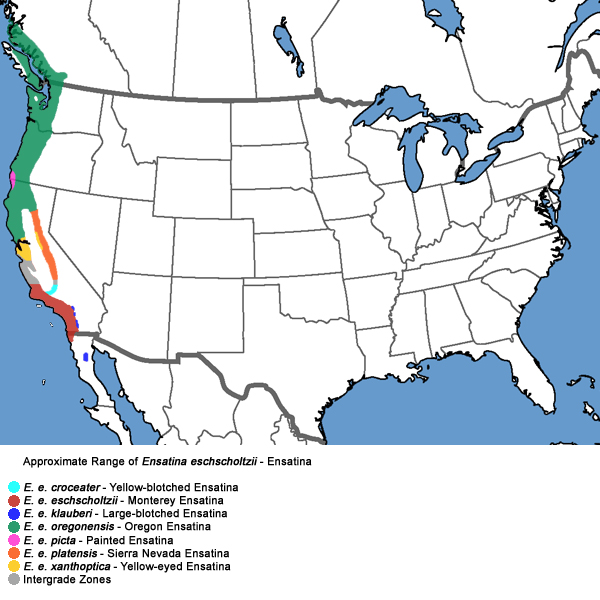

Ensatina is the most widely-distributed plethodontid salamander in the West, ranging from an isolated location in the mountains of Baja California north along the extreme northwest coast of Baja California, through most of California excluding the deserts, the central valley, and high elevations in the mountains, continuing north into Oregon and Washington west of the Cascades Mountains, and farther north into Canada along the coast of southern British Columbia. Also found on Vancouver Island.

The range maps in Stebbins (2003 and 2012) show a very large range of intergradation between 4 subspecies in Northern California that at one time was considered part of the range E. e. oregonensis. I show this range on my maps as E. e. oregonensis partly because Stebbins & McGinnis, 2012, report that molecular studies have shown complexities that make the use of the term "intergrade" inaccurate.

|

|

A population of this Ensatina subspecies exists in the Temblor Range at the extreme western edge of Kern County, much farther east than is expected due to the arid habitat. You can see the approximate location in the enlarged detail of the range map above that shows San Luis Obispo and Kern Counties, and you can see one of the salamanders in photos by Ryan Sikola farther above.

|

|

| Elevational Range |

In his 2003 field guide, Stebbins shows the elevational range of Ensatina eschscholtzii as "Sea level to around 11,000 ft (3,350 m). That is for the species but not necessarily this subspecies.

|

| Notes on Taxonomy |

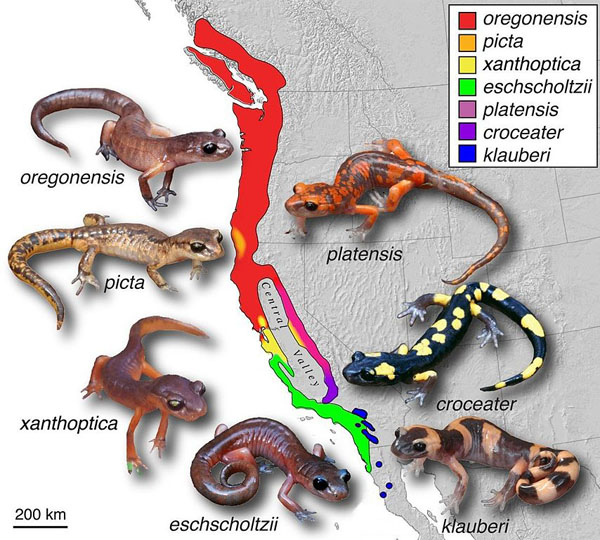

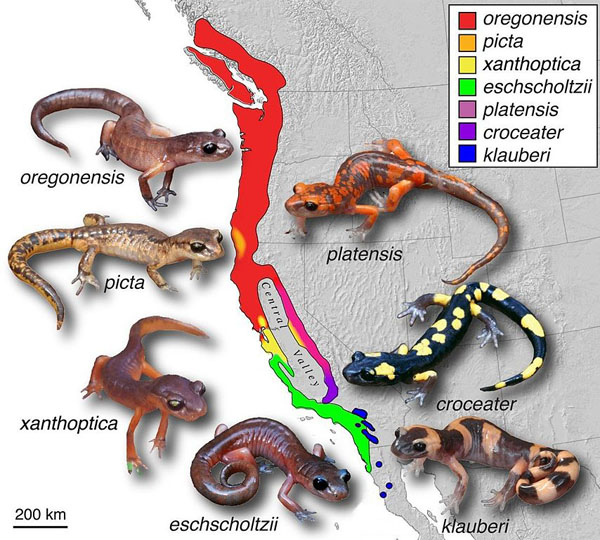

Ensatina taxonomy is controversial. The species Ensatina eschscholtzii traditionally consists of 7 subspecies:

E. e. croceater

E. e. eschscholtzii

E. e. klauberi

E. e. oregonensis

E. e. picta

E. e. platensis

E. e. xanthoptica

Some researchers see Ensatina eschscholtzii as two or more species that make up a superspecies complex.

They recognize E. e. klauberi, found at the southern end of the ring, as a separate species - Ensatina klauberi.

Ensatina as a Ring Species

Ensatina eschscholtzii has been called a "ring" species, or "Rassenkreis" (race circle) "...a connected series of neighbouring populations, each of which can interbreed with closely sited related populations, but for which there exist at least two 'end' populations in the series, which are too distantly related to interbreed, though there is a potential gene flow between each 'linked' population. Such non-breeding, though genetically connected, 'end' populations may co-exist in the same region thus closing a 'ring'." (Wikipedia, 8/26/17) The "end" populations of Ensatina are the E. e. escholtzii and the E. e. klauberi subspecies, which hybridize in San Diego County.

To learn much more about Ensatina and the ring species concept, check out this Understanding Evolution Research Profile about Tom Devitt's work.

Charles W. Brown explains the taxonomy of the Ensatina complex in detail, describing it as "a classical example of Darwinian evolution by gradualism; an accumulation of micro mutations that is now leading to the formation of a new species."

Illustration of the Ensatina ring:

Use: This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

Photo Credit: Thomas J. Devitt, Stuart J.E. Baird and Craig Moritz, 2011.

Source: (2011). "Asymmetric reproductive isolation between terminal forms of the salamander ring species Ensatina eschscholtzii revealed by fine-scale genetic analysis of a hybrid zone". BMC Evolutionary Biology 11 (1): 245. DOI:10.1186/1471-2148-11-245.

What Subspecies of Ensatina eschscholtzii Occurs in San Francisco?

Determining the taxonomy of Ensatina eschscholtzii in San Francisco County and the west side of the San Francisco Bay has been challenging:

The range maps in Stebbins, Robert C. Amphibians and Reptiles of Western North America. McGraw-Hill, 1954 and 1985 show them to be intergrades, but they do not indicate whether they itergrade with E. e. eschscholtzii or with E. e. oregonensis.

The large color range map in Thelander, Carl G., editor in chief. Life on the Edge - A Guide to California's Endangered Natural Resources - Wildlife. Berkeley: Bio Systems Books, 1994 that is based on two of Robert Stebbins' works appears to show them as intergrades with E. e. eschscholtzii, though that is not entirely clear.

The range map in Petranka, James W. Salamanders of the United States and Canada. Smithsonian Institution, 1998. shows them to be E. e. oregonensis.

The range maps in Stebbins, Robert C. A Field Guide to Western Amphibians and Reptiles Third Edition. Houghton Mifflin, 2003 and Fourth Edition 2018 are too small to show that part of the peninsula.

The range map in Joao Alexandrino, Stuart J. E. Baird, Lucinda Lawson, J. Robert Macey, Craig Moritz, and David B. Wake. Strong Selection Against Hybrids at a Hybrid Zone in the Ensatina Ring Species Complex and Its Evolutionary Implications. Evolution, 59(6), 2005, pp. 1334–1347 shows them to be E. e. oregonensis

David B. Wake. Problems with Species: Patterns and Processes of Species Formation in Salamanders. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. 93: 8–23. Published on 31 May 2006 shows a range map (click here to see it) based on a preliminary analysis from a study in progress using mitochondrial DNA in which Ensatina on the SF peninsula are shown as E. e. xanthoptica but there are E. e. oregonensis clades shown on the coast south of there. (A color map in the same paper shows the entire area west of the S.F. Bay to be E. e. oregonensis.)

The map used by Devitt, et al, 2011, shown above in their illustration of the Ensatina ring, shows them to be E. e. oregonensis.

A range map in Shawn R. Kuchta, Duncan S. Parks, David B. Wake. Pronounced phylogeographic structure on a small spatial scale: Geomorphological evolution and lineage history in the salamander ring species Ensatina eschscholtzii in central coastal California. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 50 (2009) 240–255 shows them to be E. e. xanthoptica (with E. e. oregonensis to the southwest.) (Click here to see the map.)

The range map in Stebbins, Robert C., and McGinnis, Samuel M. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Revised Edition (California Natural History Guides) University of California Press, 2012 shows them to be E. e. xanthoptica.

There are certainly more studies with more maps which I have not seen, but since some recent research shows them as E. e. xanthoptica (and photos I've seen of Ensatina from San Francisco corroborate this) I will show them as such until further research shows otherwise.

Alternate and Previous Names (Synonyms)

Ensatina eschscholtzii eschscholtzii - Monterey Ensatina (Stebbins 2003)

Ensatina eschscholtzii eschscholtzii - Monterey Salamander (Ensatina) (Stebbins 1966, 1985)

Ensatina eschscholtzii eschscholtzii - ssp. of Eschscholtz's Salamander (Stebbins 1954)

Ensatina eschscholtzii eschscholtzii - Red Salamander (Oregon Salamander) (Bishop 1943)

Ensatina eschscholtzii - Oregon Salamander (Grinnell and Camp 1917, Storer 1925)

Plethodon ensatus (Cope 1867)

Plethodon oregonensis (Girard 1856)

Heredia oregonensis (Girard 1856)

Ensatina eschscholtzii (Gray 1850)

|

| Conservation Issues (Conservation Status) |

| None |

|

|

Taxonomy |

| Family |

Plethodontidae |

Lungless Salamanders |

Gray, 1850 |

| Genus |

Ensatina |

Ensatinas |

Gray, 1850 |

| Species |

Eschscholtzii |

Ensatina |

Gray, 1850 |

Subspecies

|

eschscholtzii |

Monterey Ensatina |

Gray, 1850 |

|

Original Description |

Ensatina eschscholtzii - Gray, 1850 - Cat. Spec. Amph. Coll. Brit. Mus., Batr. Grad., p. 48

from Original Description Citations for the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Meaning of the Scientific Name |

Ensatina - Latin - ensatus = sword shaped + -ina = similar to, possibly referring to the teeth

eschscholtzii - honors Johann F. Eschscholtz

from Scientific and Common Names of the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America - Explained © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Related California Salamanders |

Large-blotched Ensatina

Oregon Ensatina

Painted Ensatina

Sierra Nevada Ensatina

Yellow-eyed Ensatina

Yellow-blotched Ensatina

|

|

More Information and References |

California Department of Fish and Wildlife

AmphibiaWeb

Hansen, Robert W. and Shedd, Jackson D. California Amphibians and Reptiles. (Princeton Field Guides.) Princeton University Press, 2025.

Stebbins, Robert C., and McGinnis, Samuel M. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Revised Edition (California Natural History Guides) University of California Press, 2012.

Stebbins, Robert C. California Amphibians and Reptiles. The University of California Press, 1972.

Flaxington, William C. Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Field Observations, Distribution, and Natural History. Fieldnotes Press, Anaheim, California, 2021.

Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025. Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with Comments Regarding Confidence in Our Understanding. Ninth Edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. [SSAR] 87pp.

Samuel M. McGinnis and Robert C. Stebbins. Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles & Amphibians. 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2018.

Stebbins, Robert C. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003.

Behler, John L., and F. Wayne King. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant, and Joseph T. Collins. Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Powell, Robert., Joseph T. Collins, and Errol D. Hooper Jr. A Key to Amphibians and Reptiles of the Continental United States and Canada. The University Press of Kansas, 1998.

American Museum of Natural History - Amphibian Species of the World 6.2

Bartlett, R. D. & Patricia P. Bartlett. Guide and Reference to the Amphibians of Western North America (North of Mexico) and Hawaii. University Press of Florida, 2009.

Bishop, Sherman C. Handbook of Salamanders. Cornell University Press, 1943.

Lannoo, Michael (Editor). Amphibian Declines: The Conservation Status of United States Species. University of California Press, June 2005.

Petranka, James W. Salamanders of the United States and Canada. Smithsonian Institution, 1998.

Joao Alexandrino, Stuart J. E. Baird, Lucinda Lawson, J. Robert Macey, Craig Moritz, and David B. Wake. Strong Selection Against Hybrids at a Hybrid Zone in the Ensatina Ring Species Complex and Its Evolutionary Implications. Evolution, 59(6), 2005, pp. 1334–1347.

Shawn R. Kuchta, Duncan S. Parks, David B. Wake. Pronounced phylogeographic structure on a small spatial scale: Geomorphological evolution and lineage history in the salamander ring species Ensatina eschscholtzii in central coastal California. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 50 (2009) 240–255

|

|

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the July 2025 State of California Special Animals List and the July 2025 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists, but they don't change a great deal from year to year.. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists:

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals.

A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page.

If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings.

Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website.

This salamander is not included on the Special Animals List, which indicates that there are no significant conservation concerns for it in California.

|

| Organization |

Status Listing |

Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking |

|

|

| NatureServe State Ranking |

|

|

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) |

None |

|

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) |

None |

|

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

None |

|

| Bureau of Land Management |

None |

|

| USDA Forest Service |

None |

|

| IUCN |

|

|

|

|

|