|

|

|

| Adult, Contra Costa County |

Adult, Napa County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, San Luis Obispo County |

Adult, Contra Costa County |

Underside of Adult, Contra Costa County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Contra Costa County |

Adult, Contra Costa County |

Adult, Los Angeles County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Contra Costa County |

Adult, Contra Costa County |

Male in aquatic phase, Kern County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Napa County |

Adult swimming in pond,

Contra Costa County |

Terrestrial phase adult, San Diego County © Chris Gruenwald |

|

|

|

|

| Adult from the Santa Ana Mountains, Riverside County © Nathan Ray |

Adult, Los Angeles county

© Jonathan Nemati |

Adult, underwater, Solano County

© Sean Barry |

Adult, Santa Ana Mountains, Orange County © Benjamin Smith |

|

|

|

|

Adult, Sonoma County

© egret.org / Audubon Canyon Ranch |

Adult found in water in June, long after the breeding season. Newts that remain in the water after breeding do not have the smooth skin and wide paddle-like tail, but their normal flat tail still helps them swim. © egret.org / Audubon Canyon Ranch

|

This newt was also found in water long after the breeding season. It has a water-logged appearance, but the skin is still rough as it is with terrestrial newts.

© egret.org / Audubon Canyon Ranch

|

|

|

|

|

| A newt in a hole close to the breeding pond. |

Adult, Marin County © Andre Giraldi |

Adult California Newt with sympatric adult and juvenile Yellow-eyed Ensatina for comparison. Santa Clara County

© Cait Hutnik |

|

|

|

|

| This bucket full of California Newts and Yellow-eyed Ensatinas was part of a 2021 pitfall trap study on a Santa Clara County road with a high mortality of salamanders caused by traffic. Almost 40 percent of newts that attempted to cross the road during the rainy-season to get from their dry-season upland habitat to their breeding grounds were killed by vehicles. Salamanders that fell into temporary traps at night, including those seen in the bucket here, were counted and released the next morning. As a result of the study, newt crossings will be constructed in the area. © Ariel Starr |

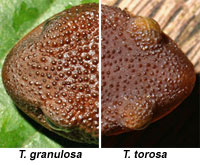

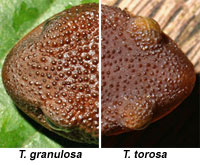

When seen from above, the eyes of

a California Newt, T. torosa, extend to or beyond the margin of the head.

Compare with T. granulosa, the Rough-skinned Newt, on the left and with other newts found in California here:

Newt Identification.

|

© Regan Sikola

Top: Rough-skinned Newt

Bottom: California Newt

This is a good illustration of how the eyes don't extend past the margin

of the head on T. granulosa

but they do on T. torosa. |

|

| |

|

|

|

Juveniles |

|

|

|

|

| Juvenile, Kern County |

Juvenile, Los Angeles County

© Jeff Ahrens |

Adult and juvenile, Contra Costa County |

Adult and juvenile, Contra Costa County |

|

|

|

|

Juvenile, Los Angeles County

© Jeff Ahrens |

This incredible collection of hundreds or perhaps thousands of juvenile newts was found in Napa County in late September under a boat near a lake that had a small amount of water remaining in it during a year of severe drought. No newts were found at the same location four days previously. Two species of newts are found at the location, California Newts, and Rough-skinned Newts. Some of them appear to be California Newts, but it's not possible to know the species of all of them.

Recently-transformed newts sometimes gather into masses

in order to help them retain moisture which can be lost through the skin.

© Anonymous |

|

| |

|

|

|

| Feeding |

|

|

|

|

| Adult newt eating a very large worm in Mendocino County © Amelia True |

|

|

|

|

|

| These newts appear to be stretching an earthworm and struggling to see which one gets to eat it. Alameda county © Scott Futral |

This short video shows a male California Newt underwater in an Alameda County breeding pond eating an earthworm. © Mark Gary

|

|

| |

|

|

Newt Predation |

|

|

|

Dead adult newts in breeding pond in January, Alameda County © Mark Gary

California Newts are very toxic, so much so that most animals that try to eat them will get sick or die. Nevertheless, some unknown predator has been killing and eating newts in this pond. Five predated newt carcasses were observed. During the breeding season newts are often out in the open and easy to prey on at the edge of the water. Some gartersnakes can eat newts but they swallow their prey whole. The predators of these newts appear to have torn them open and eaten only part of the newts, perhaps only the parts that contain little or no toxins. |

Adult Terrestrial Gartersnake eating a California Newt in San Luis Obispo County

© Ryan Sikola

You can read about gartersnakes eating toxic newts below. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This Diablo Range Gartersnake was observed in October eating a toxic California Newt in Alameda County at the edge of a newt breeding pond. You can see the snake biting the tail, then swallowing the newt tail first and then the head. You can read about gartersnakes eating toxic newts here. © Mark Gary

|

|

|

|

|

|

| This tiny juvenile Diablo Range Gartersnake was observed in December eating a recently-transformed juvenile California Newt on the edge of the same newt breeding pond in Alameda County where the adult snake above was observed eating an adult newt. © Mark Gary |

|

| |

|

|

|

Defensive Posture |

|

|

|

|

Adult in "unkenreflex" defensive posture in which the brightly-colored underside is displayed as a warning. Santa Cruz County

The California Newt holds its tail mostly straight out behind its body in this posture.

Compare with the curled tail of the sometimes sympatric Rough-skinned Newt.

|

Adult, Santa Cruz County,

in defensive posture. |

|

|

|

| Aberrant California Newts |

|

|

|

This unusually pigmented adult newt was photographed in Santa Cruz County © Mary Yan.

It appears to be missing its dark pigment, but the eyes are dark so it's not an albino, it's leucistic or hypomelanistic.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| This adult covered with warts was found in a creek in San Luis Obispo County in mid September. A population of newts in San Diego is also covered with "warts" that are caused by disease, which may be what is causing this newt's unusual appearance. © Anonymous |

|

|

|

|

|

| This adult newt has all black eyes. It was found just north of the Middle Fork of the Kaweah River in Tulare County, where newts have been identified as mostly Taricha torosa, but since it is in the hybrid zone with Taricha sierrae, it could be either species or a hybrid. Both of these species typically have patches of gold coloring in the eyes. © Caitlin Kupar |

|

|

|

|

|

This unusually pale-skinned blotched newt was found in Santa Clara County

© Cait Hutnik

(See more pictures of this newt on Cait's website.)

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Breeding, Eggs, and Larvae |

|

|

|

|

| Mass of underwater breeding adults, Contra Costa County |

Eggs, close-up |

Larva in late June, Alameda County |

|

Here are lots more pictures of breeding season newts, breeding habitats, eggs and larvae.

|

| Habitat |

|

|

|

|

| Habitat, Contra Costa County |

Habitat, Contra Costa County |

Breeding pond, Contra Costa County |

Habitat, Alameda County |

|

|

|

|

| Habitat, San Luis Obispo County |

Habitat, Contra Costa County |

Habitat, Contra Costa County |

Habitat, San Diego County |

|

|

|

|

Habitat, San Gabriel Mountains,

Los Angeles County |

Habitat, Kern County |

Habitat, 1500 ft., San Gabriel Mountains, Los Angeles County |

Habitat, 1400 ft., San Gabriel Mountains, Los Angeles County |

|

|

|

|

| Habitat, Winter, Contra Costa County |

These East Bay hills are full of newts, Alameda County |

Several newts were found under these rocks in spring, Alameda County. |

Habitat, Contra Costa County |

|

|

|

|

Kaweah River as it enters Lake Kaweah, Tulare County.

In the Sierra Nevada, California Newts are found south of the Kaweah River, while Sierra Newts are found north of the river. However, there is some overlap between the two around the river itself. |

Habitat, San Gabriel Mountains, Los Angeles County © Jonathan Nemati |

Habitat, Alameda County |

|

|

|

|

Habitat, Los Angeles County

© Jeff Ahrens |

Habitat, Los Angeles County

© Jeff Ahrens |

A careful look underneath the fallen branches and bark of the dead tree shown above on a wet winter afternoon turned up 16 salamanders of 4 species - one Arboreal Salamander, two Coast Range Newts, one Yellow-eyed Ensatina, and 12 California Slender Salamanders, proving that wood debris on a forest floor is an important microhabitat for salamanders. Along with fallen debris, tree bark, tree cavities, root holes, and splits in trees are also useful habitat for many kinds of wildlife, including birds, mammals, amphibians and reptiles, but dead trees and their debris are often removed indiscriminately without consideration for wildlife.

The Cavity Conservation Initiative is a group whose goal is to educate land managers and the public about the value of dead trees. |

|

|

|

|

| Habitat, Contra Costa County |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

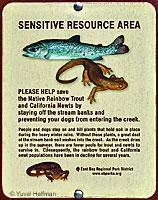

Newt Conservation |

|

|

|

|

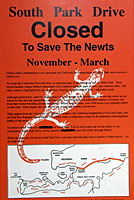

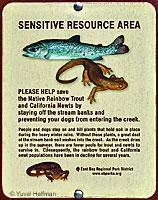

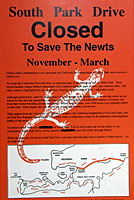

Signs indicating a road closure to protect newts as they migrate to

and from breeding areas during the rainy season, Contra Costa County.

|

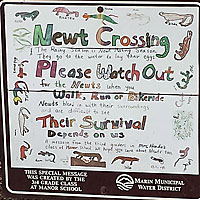

Marin County sign made by Mrs. Honda's third grade class at Manor school. |

|

|

|

|

| Sign at dried up breeding pond in November, Contra Costa County |

Same sign in late January in a full pond during a wet winter.

|

Sign in Marin County |

|

|

|

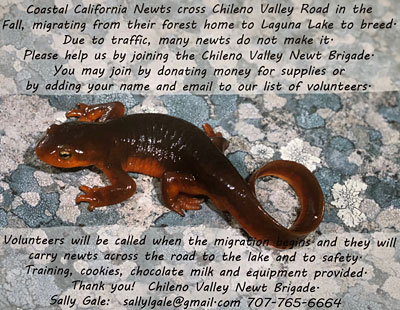

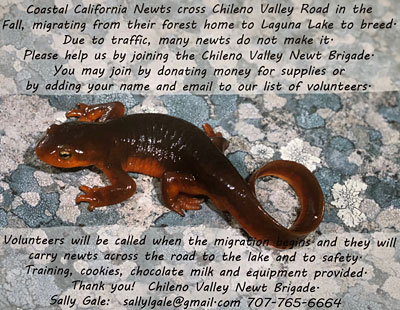

| The Chileno Valley Newt Brigade was organized to help ferry migrating newts across a road in Marin County. |

Alameda County sign © Yuval Helfman |

| |

|

|

| Short Videos |

|

|

|

|

California Newts on the move in the woods on a Fall morning.

|

A big ball of newts forms in the breeding pond when a male and female in amplexus are approached by several male newts who want to take the female. |

Male and female newts in amplexus in the breeding pond. The males hold on tight and swim around the pond using their huge tails. One uses the toes on his hind feet to stroke a female, probably to make her receptive to take his spermatophore. |

Views of a large mass of female newts in the breeding pond, as they go about laying and securing their eggs. |

|

|

|

|

| Female newts repeatedly attack and bite at newt egg sacs, probably in an attempt to eat them. Newts have been known to eat the eggs of their own kind. |

Solitary male newts patrol the edge of the pond at the beginning of the breeding season, waiting for females to arrive. Females are seen crawling overland and entering the water. |

This short video shows a male California Newt underwater in an Alameda County breeding pond eating an earthworm.

© Mark Gary

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Description |

| |

| Size |

Adults are 2 3/4 - 3 1/2 inches long (7 - 8.9 cm) from snout to vent, and 4.9 - 7.8 inches (12.5 -20 cm) in total length.

|

| Appearance |

A stocky, medium-sized salamander with rough, grainy skin in the terrestrial phase, and no costal grooves.

|

| Color and Pattern |

Terrestrial adults are yellowish-brown to dark brown above, pale yellow to orange below.

(There is less contrast between dorsal and ventral color on sides than with T. granulosa.)

The eyelids and the area below the eyes are lighter than the rest of the head.

The iris is silvery to pale yellow.

The eyes appear to extend to or beyond the outline of the head when viewed from above, (unlike T. granulosa.)

|

| Male / Female Differences |

| Breeding males develop smooth skin that looks wrinkled and baggy underwater, a flattened tail to aid with swimming, a swollen cloaca, and rough nuptial pads on the undersides of the feet to aid in holding onto females during amplexus. |

| Larvae |

Aquatic larvae are the pond type, light yellow above with two dark regular narrow bands on the back.

|

| Comparison With Similar Species of Newts |

Identifying Species of Pacific Newts - Genus Taricha

|

| Life History and Behavior |

Rough-skinned when in the terrestrial phase.

Breathes through lungs. |

| Activity |

Terrestrial and diurnal, often seen crawling over land in the daytime, becoming aquatic when breeding.

In some permanent bodies of water, adults retain their aquatic breeding phase characteristics (smooth skin, flattened tail) and live in the water year-round.

Sometimes seen moving in large numbers to aquatic breeding sites during or after rains during breeding season.

Terrestrial newts spend the hot dry summer in moist habitats under woody debris, or in rock crevices and animal burrows, but can sometimes be seen wandering overland in moist habitat or conditions any time of the year. |

| Longevity |

| Longevity is not known, but it has been estimated that California Newts can live for more than 20 years. (Amphibiaweb) |

| Defense |

When threatened, a newt will assume a sway-backed defensive pose, closing its eyes, extending its limbs to the sides, and holding its tail straight out. This "unken reflex" exposes its bright orange ventral surface coloring which is a warning to potential predators that the newt is poisonous.

Toxic Secretions

Adult California Newts have poisonous skin secretions containing the powerful neurotoxin tetrodotoxin that repel most predators. The poison is widespread throughout the skin, ovaries, muscles, and blood, and is also present in the egg masses and embryos. (The liver, viscera, and testes contain only very small amounts so they can probably be eaten.) The toxin can cause death in many animals, including humans, if eaten in sufficient quantity. (One study estimated that 25,000 mice could be killed from the skin of one Rough-skinned newt, the most toxic of the Taricha species. (Taricha torosa is about 10 percent as toxic as T. granulosa.)

The poison can also be ingested through a mucous membrane or a cut in the skin, so care should always be taken when handling adult newts and their eggs.

Larvae are not poisonous and are preyed on by adult newts and other predators.

Chemical cues from adult newts trigger larvae to seek cover.

|

Newt Predators |

Gartersnakes

In most locations the Common Gartersnake, Thamnophis sirtalis, has a high resistance to tetrodotoxin which allows it to prey on Pacific Newts, genus Taricha. Thamnophis atratus and Thamnophis couchii have also been found with a strong resistance to tetrodotoxin that allows them to eat Pacific Newts.

Thamnophis elegans has also been found eating Taricha torosa in San Luis Obispo County.

(Feldman, Hansen, & Sikola. Herpetological Review 51[3] 2020.)

An arms race between T. sirtalis and the tetrodoxin poison contained in Taricha has been documented, with newt toxicity varying by location and snake resistance to the toxin also varying by location.

(Edmund D. Brodie III. Patterns, Process, and the Parable of the Coffeepot Incident: Arms Races Between Newts and Snakes from Landscapes to Molecules. From In the Light of Evolution: Essays from the Laboratory and Field edited by Jonathan Losos (Roberts and Company Publishers). 2010.)

The Bay Area is the Center of an Evolutionary Race Between Hungry Snakes and Toxic Newts.

by Anton Sorokin. Bay Nature, April 6, 2022

Other Pacific Newt Predators

"...in southern California, two introduced predators, crayfish and mosquitofish, are causing serious [newt] declines ... via predation on egg masses and larvae."

(Kuchta, 2005)

"Jennings and Cook (1998) found that introduced bullfrogs (Rana catesbeiana) in Sonoma and Riverside counties not only eat larval California newts, but surprisingly also adults. Kats et al. (1998)"

(Kuchta, 2005)

Great Blue Herons are known to prey on newts by swallowing them whole. (Fellers et al., 2008)

Otters have been observed preying on Rough-skinned Newts in Oregon (Stokes, Northwestern Naturalist 96(1), 2015).

Stokes et al, 2011, speculate that Ravens, crows and other Corvids may also contribute to newt predation as well as small carnivorous mammals such as skunks and raccoons, though they had no evidence yet to prove this.

(Amber N. Stokes, David G. Cook, Charles T. Hanifin, Edmund D. Brodie III, and Edmund D. Brodie Jr. Sex-biased Predation on Newts of the Genus Taricha by a Novel Predator and its Relationship with Tetrodotoxin Toxicity. The American Midland Naturalist 165(Apr 2011):389-399.) |

| Sounds |

According to Davis and Brattstrom, California Newts produce a repertoire of sounds. (Davis, J. R. and B. H. Brattstrom. 1975. Sounds produced by the California newts, Taricha torosa. Herpetologica 31:409-412.) The sounds are very faint and difficult to hear over environmental sounds in the field. They did not determine how the newts were able to physically produce these different sounds. Breeding phase Coast Range Newts from Orange County were observed and recorded in a laboratory in a naturalistic setting where they were able to continue their typical social behaviors.

Three types of sounds were documented: clicks, squeaks, and whistles.

Clicks were the most commonly heard sounds. They were made when newts were put in an unfamiliar location, and when they were confronted by another newt. (The clicks appeared to be used to establish territories.)

Squeaks were made when a newt was picked up, and were sometimes accompanied by the newt twisting its body. The purpose of the squeak might be to startle a predator or to advertise the newt's toxicity.

Whistles were observed during breeding activity when a newt was touched in the middle of the back by a human or another newt, such as when a male newt climbed onto the back of another male newt. It was produced by males and females. The sound was not observed and could not be artificially evoked two weeks after breeding was over. This sound appears to be used in sex recognition and to establish hierarchical relationships, similar to the release call of a frog. |

| Diet and Feeding |

Adults eat small invertebrates such as worms, snails, slugs, sow bugs, and insects. They also consume amphibian eggs and larvae, including newt larvae and newt eggs. A small nestling bird was found in the stomach of one newt.

When feeding on the ground, adults feed by projecting a sticky tongue to capture prey. Aquatic adults open their mouth and suck the prey in.

Larvae eat small aquatic invertebrates, decomposing organic matter, and possibly other newt larvae.

|

| Reproduction |

Reproduction is aquatic.

Adults probably reach reproductive maturity in their third year.

The breeding season lasts 6 - 12 weeks.

Adults migrate from locations on land to ponds, reservoirs, and sluggish pools in streams to breed, typically beginning anywhere from late December to February, depending on rainfall amounts.

Populations that breed in stream pools migrate later, typically in March and April, after the stream flooding has subsided.

Migration may take several weeks and cover large distances. (In one study, newts were recaptured up to nearly two miles (3,200 m) away from the breeding pond where they were originally captured and marked.)

Newts have a strong homing instinct and typically return to the same breeding site each time they breed. This homing behavior has not been explained, but experiments show that it involves a sense of their body position, but it could also involve the sense of smell or a form of celestial navigation.

Males arrive first, and stay longer than females.

In the water, males transform into their aquatic phase, with smooth skin that lightens in color, swollen cloacal lips, and tails enlarged and flattened to help them swim. Females develop smoother skin, but do not undergo as much change as males.

Males patrol the edges of the breeding pond waiting from females to enter the water. When a female enters, she may be mobbed by a number of males who struggle to hold on to her until one male grabs on and cannot be removed.

After a period of amplexus, where the male clutches the female from above, the male deposits a spermatophore and the female picks it up with her cloaca. |

| Eggs |

Females lay and attach a spherical egg mass to submerged vegetation, branches, or rocks.

Southern populations tend to lay egg masses under rocks in quiet stream pools where northern and central populations tend to attach egg masses to vegetation.

Egg masses contain from 7 - 47 eggs. It is estimated from ovarian counts of 130 - 160 that females lay from 3 - 6 masses each.

Egg masses are attached just below the surface of the water. If the water rises significantly or lowers and strands the eggs, the eggs will die.

Incubation times may vary at various locations, from 14 - 52 days. |

| Larvae |

The larval stage lasts several months.

The average larval period at one location in the Bay Area was observed to be from March to October.

Larvae transform and begin to live on land at the end of the Summer or in early Fall.

Overwintering Larvae

Overwintering by T. torosa larvae is not common, but a few examples have been documented.

Larvae that were completing their metamorphosis were observed in April and May in Southern California in 1909. (Storer, 1925, cited by Kuchta on Amphibiaweb.)

(Typically those larvae would have transformed in the previous Summer or early Fall if they had not overwintered.)

Overwintering larvae were also observed in Riverside County in April 2001 (Herpetological Review 36(3), 2005)

Owen Holt found an overwintering larva in

Santa Clara County on March 12th, 2020. (Personal communication.)

You can see a picture of the larva on the T. torosa Breeding, Eggs, and Larvae page.

Metamorphosis

Metamorphosis may be triggered by pond drying in some waters, but other factors that influence metamorphosis have not been determined.

Metamorphosis takes about 2 weeks, as the tail fin is absorbed and the gills are reduced.

Transformed juveniles leave the water with adult coloration and characteristics and with a trace of gills remaining.

At this time they cannot survive if kept in the water.

Juveniles leave the natal pond and travel overland where it is assumed they take refuge and do not return to the water until they breed.

|

| Habitat |

Found in wet forests, oak forests, chaparral, and rolling grasslands. In southern California, drier chaparral, oak woodland, and grasslands are used.

|

| Geographical Range |

Endemic to California.

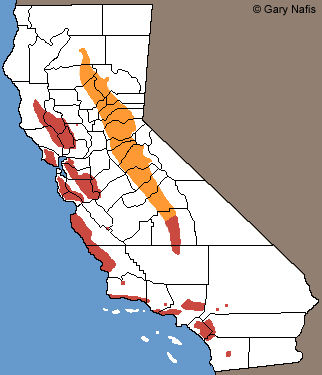

Found along the coast and coast range mountains from Mendocino county south to San Diego county.

A disjunct population is found in the southern Sierra Nevada from northern Kern county at Breckenridge Mountain north to a zone of hybridization with the Sierra Newt along the Kaweah River in Tulare County.

(Formerly, newts throughout all of the Sierra Nevada were recognized as a different subspecies, T. t. sierra - Sierra Newt, which is now known to range only north of the range of this species in the Sierra Nevada.)

Reports of sightings from northwestern Baja California have never been verified. (Kuchta, 2005)

Co-exists with T. granulosa from Santa Cruz county north to Mendocino county.

|

| Elevational Range |

From sea level to 4,200 ft. (1,280 m.) on Mt. Hamilton. (Stebbins & McGinnis 2012)

|

| Notes on Taxonomy |

Two subspecies of Taricha torosa have been traditionally recognized: T. t. sierrae, and T. t. torosa. In 2007, Shawn R. Kuchta1 showed that the two subspecies of Taricha torosa "constitute distinct evolutionary lineages and merit recognition as separate species: T. torosa (California newt) and T. sierrae (Sierra newt). " The contact zone between these two species is the southern Sierra Nevada with a "hybrid zone centered along the Kaweah River in Tulare County."

Genetic variation exists between newts found north and south of the Salinas Valley.

"Warty Newts"

A geographically isolated population of T. torosa in San Diego county has very warty skin and was once recognized as either a different species

T. klauberi, or as a different subspecies T. t. klauberi, the Warty Newt, but "...it was later determined that the warty phenotype was pathological..."

(Kuchta, 2005)

Analysis has determined that these San Diego county newts are "genetically differentiated, demographically independent, geographically disjunct, and have a history of isolation relative to the coastal populations." (Shawn Kuchta and An-Ming Tan, 2006)

Warty newts have also been reported from the San Francisco Peninsula and from Atascadero.

Alternate and Previous Names (Synonyms)

San Diego County populations: Triturus klauberi - Warty Newt (Bishop 1943)

Taricha torosa - Coast Range Newt (Stebbins & McGinnis 2012)

Taricha torosa torosa - Coast Range Newt (Stebbins 1966, 1985, 2003)

Taricha torosa torosa - ssp. of California Newt (Stebbins 1954)

Triturus torosus - California Newt (Bishop 1943)

Triturus torosus - Pacific Coast Newt (Brown Water Dog) (Storer 1925)

Notophthalmus torosus - Pacific Coast Newt - Western Newt, Warty Salamander, Water-Dog, Capt. Beechey's Salamander, Pacific Water-lizard, California Newt, Sad-colored Anaides (Grinnell and Camp, 1917)

Taricha laevis (Baird & Girard 1853)

Notophthalmus torosus (Baird 1850)

Salamandra Beecheyi (Gray 1839)

Triturus torosus - (Rathke 1833)

|

| Conservation Issues (Conservation Status) |

Protected from take with a sport fishing license in 2013.

Some verified populations in San Diego County are now extinct. Southern California populations have suffered population declines due to habitat loss and alteration caused by human activity, and from introduced predatory mosquitofish, crayfish, and bullfrogs, which eat the non-poisonous larvae and eggs. Breeding ponds have been destroyed for development, and stream pools used for breeding have been destroyed by sedimentation caused by wildfires.

Road mortality causes population declines in areas where newts must cross well-travelled roads during their breeding migrations. Slowly-moving newts on a road are hard to see and avoid, especially when they are moving at night,

A newt mortality study published in 2021 showed that more than 39 percent of newts crossing a road in Santa Clara County were killed and predicted they might be extirpated there in 57 years.

(Alma Bridge Road-Related Newt Mortality Study. H. T. Harvey & Associates, November 12, 2021.)

Community Efforts to Protect Migrating Newts (pictures above)

The Chileno Valley Newt Brigade was created to help ferry migrating newts across a road in Marin County by local activists.

The East Bay Regional Park District has closed South Park Drive in Tilden Park to all motor vehicle traffic every year during the rainy season for several decades.

|

|

| Taxonomy |

| Family |

Salamandridae |

Newts |

Goldfuss, 1820 |

| Genus |

Taricha |

Pacific Newts |

Gray, 1850 |

Species

|

torosa |

California Newt |

(Rathke, in Eschscholtz, 1833) |

|

Original Description |

Rathke, 1833 - in Eschscholtz, Zool. Atlas, Pt. 5, p. 12, pl. 21, fig. 15

from Original Description Citations for the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Meaning of the Scientific Name |

Taricha - Greek = preserved mummy, possibly referring to the rough skinned appearance

torosa - Latin = full of muscle, fleshy - referring to the thick head and body

from Scientific and Common Names of the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America - Explained © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Related California Salamanders |

Taricha sierrae - Sierra Newt

Taricha rivularis - Red-bellied Newt

Taricha granulosa - Rough-skinned Newt

|

|

More Information and References |

California Department of Fish and Wildlife

AmphibiaWeb

Hansen, Robert W. and Shedd, Jackson D. California Amphibians and Reptiles. (Princeton Field Guides.) Princeton University Press, 2025.

Stebbins, Robert C., and McGinnis, Samuel M. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Revised Edition (California Natural History Guides) University of California Press, 2012.

Stebbins, Robert C. California Amphibians and Reptiles. The University of California Press, 1972.

Flaxington, William C. Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Field Observations, Distribution, and Natural History. Fieldnotes Press, Anaheim, California, 2021.

Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025. Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with Comments Regarding Confidence in Our Understanding. Ninth Edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. [SSAR] 87pp.

Samuel M. McGinnis and Robert C. Stebbins. Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles & Amphibians. 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2018.

Stebbins, Robert C. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003.

Behler, John L., and F. Wayne King. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant, and Joseph T. Collins. Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Powell, Robert., Joseph T. Collins, and Errol D. Hooper Jr. A Key to Amphibians and Reptiles of the Continental United States and Canada. The University Press of Kansas, 1998.

American Museum of Natural History - Amphibian Species of the World 6.2

Bartlett, R. D. & Patricia P. Bartlett. Guide and Reference to the Amphibians of Western North America (North of Mexico) and Hawaii. University Press of Florida, 2009.

Bishop, Sherman C. Handbook of Salamanders. Cornell University Press, 1943.

Lannoo, Michael (Editor). Amphibian Declines: The Conservation Status of United States Species. University of California Press, June 2005.

Petranka, James W. Salamanders of the United States and Canada. Smithsonian Institution, 1998.

Shawn R. Kuchta. Taricha Torosa. Amphibian Declines: The Conservation Status of United States Species, edited by Michael Lannoo. UC Press. 2005

Jones, Lawrence L. C. , William P. Leonard, Deanna H. Olson, editors. Amphibians of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle Audubon Society, 2005.

1Herpetologica, 63(3), 2007, 332–350 E 2007 by The Herpetologists’ League, Inc.

Contact Zones and Species Limits: Hybridization Between Lineages of the California Newt, Taricha torosa, in the southern Sierra Nevada

Shawn R. Kuchta

2 Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2006, 89, 213–239. With 8 figures

Lineage diversification on an evolving landscape: phylogeography of the California newt, Taricha torosa (Caudata: Salamandridae)

Shawn R. Kuchta and An-Ming Tan

Joseph Grinnell and Charles Lewis Camp. A Distributional List of the Amphibians and Reptiles of California. University of California Publications in Zoology Vol. 17, No. 10, pp. 127-208. July 11, 1917.

Shawn R. Kuchta. Amphibian Declines: The Conservation Status of United States Species, edited by Michael Lannoo. University of California Press. 2005

|

|

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the July 2025 State of California Special Animals List and the July 2025 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists, but they don't change a great deal from year to year.. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists:

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals.

A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page.

If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings.

Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website.

The CA Department of Fish and Wildlife listing refers to Coast Range Newts from Monterey County & south only.

Newts north of Monterey County and in the Sierra Nevada are not listed as a Species of Special Concern.

|

| Organization |

Status Listing |

Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking |

G4 |

Apparently Secure—Uncommon but not rare; some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors. |

| NatureServe State Ranking |

S4 |

Apparently Secure—Uncommon but not rare in the state; some cause for long-term concern due to

declines or other factors. |

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) |

None |

|

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) |

None |

|

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

SSC |

California Species of Special Concern |

| Bureau of Land Management |

None |

|

| USDA Forest Service |

None |

|

| IUCN |

Not listed |

|

|

|

|

Red: Range of this species in California

Red: Range of this species in California