|

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Mendocino County |

|

|

|

| Adult, Mendocino County |

Adult, Humboldt County |

|

|

|

| Adult, Del Norte County, showing white defensive secretions on the tail and on the parotoid gland behind the eye |

|

|

|

Adult, Del Norte County

© Alan Barron |

Sub-adult, Del Norte County

© Alan Barron |

Adult, Del Norte County

© Alan Barron |

|

|

|

| Adult, Mendocino County, in defensive position, excreting milky secretions from head, sides, and tail © Val Johnson |

Humboldt County adult in extreme defensive pose, excreting white fluid from the parotoid glands. © Grayson Sandy

|

|

|

|

Adult, Humboldt County

© Marcus Rehrman |

Adult, Humboldt County © Spencer Riffle |

Adult, Del Norte County © Ryan Sikola |

|

|

|

| The large adult shown above from Humboldt County measures a little more than 9 inches in total length (23 cm) which could be a size record. (22 cm is the size record I have found.) © Pouya Kazemi |

|

|

|

Adult, Sonoma County

© Andre Giraldi |

Adult, Humboldt County

© Zachary Cava |

|

| |

|

|

| Northwestern Salamanders From Outside California |

|

|

|

| |

Adult, King County, Washington |

|

|

|

|

| Recently-transformed juvenile |

Adult, Snohomish County, Washington |

Adult, Snohomish County, Washington |

| |

|

|

| |

Recently-transformed juvenile,

King County, Washington |

|

| |

|

|

| Neotenic Adults |

|

|

|

|

A large adult with reduced gills, 5,700 ft., Pierce county, Washington, found on land at the edge of a lake.

This salamander appears to be transforming from an aquatic to a terrestrial existence. |

|

|

|

Large aquatic adult, 5,700 ft.,

Pierce county, Washington |

Adult male during the breeding season, showing a swollen vent. |

Neotenic or paedomorphic adult, from near sea level in King County, Washington. |

|

|

|

Large old aquatic neotenic adult in high-altitude lake, 5,700 ft.,

Pierce County, Washington |

|

| |

|

|

| Aberrant Adult |

|

|

This leucistic or amelanistic paedomorph adult was found in Humboldt County. Notice the prominent parotoid glands.

© Zachary Vegso |

| |

|

|

| Eggs, Larvae, & Juveniles - See More Pictures |

|

|

|

| Egg mass attached to a stick that was submerged in a small pond |

Larva in water

|

Recently-transformed juvenile 10.5 months after hatching |

| |

|

|

| Habitat |

|

|

|

| Habitat, Mendocino County |

Redwood forest habitat,

Humboldt County |

Habitat, breeding pond,

Del Norte County |

|

|

|

| Habitat, Humboldt County |

Habitat, Humboldt County |

Breeding pond, Pacific

County, Washington |

|

|

|

| Breeding habitat in early March, Humboldt County |

|

More pictures of eggs, larvae, and breeding habitat - Page 2.

More pictures of this salamander and its natural habitat are available on our Northwest Herps page.

|

| Short Videos |

|

|

|

| An adult Northwestern Salamander paedomorph (still has gills and lives in water permanently - never transformed to live on land) swims around in a shallow pan of water. It's motion is slowed down at the end to showoff its graceful movement. |

A look at a breeding pond during the February breeding season, including several egg masses, and a paedomorph in the water at night. |

|

|

|

|

| Description |

| |

| Size |

Terrestrial adults are 3 - 5 1/5 inches long (7.6 - 13.2 cm) from snout to vent, (Stebbins, 2003)

and 14-22 cm (5.5 to 8.7 inches) total length. (Boundy and Balgooyen 1988).

Neotenic adults (aquatic adults with gills) grow up to 26 cm (10.2 inches) in total length. (Boundy and Balgooyen 1988).

|

| Appearance |

A large, heavy, stout bodied lunged salamander with a short broad rounded head, blunt snout, small protuberant eyes, moist smooth skin with conspicuous oval parotoid glands behind the eyes and on the tail ridge.

Usually 11 costal grooves, no nasolabial grooves. The tail is flattened from side to side.

Adults occur in an aquatic gilled form, and as a fully-transformed terrestrial form with lungs. |

| Color and Pattern |

Dark brown, gray, or black.

Populations far north of California may have cream or yellow flecks on dorsum.

|

| Life History and Behavior |

A member of the Mole Salamander family (Ambystomatidae) whose members are medium to large in size with heavy, stocky bodies.

Ambystomatid salamanders have two distinct life phases:

- Larvae hatch from eggs laid in water where they swim using an enlarged tail fin and breathe with filamentous external gills. - Aquatic larvae transform into four-legged salamanders that live on the ground and breathe air with lungs.

In some cases adults do not transform from the aquatic larval stage to a terrestrial form, instead they stay in the water throughout their lives where they grow legs, reach adult size and breed, but retain their gills and finned tails.

This retention of juvenile features in an adult is called either paedomorphosis (also spelled pedomorphosis) or neoteny.

Adults are paedomorphic or paedomorphs, or neotenic adults and they are facultative paedomorphs - meaning that some individuals metamorphose while others do not. (There are some Ambystomatid species elsewhere where individuals never undergo metamorphosis. These are called obligate paedomorphs.) |

| Activity |

Adults spend much of their lives underground, often utilizing the tunnels of burrowing mammals such as moles and ground squirrels.

Transformed adults are most likely to be seen on rainy nights during migrations over land to and from breeding sites, or in water when breeding in ponds, lakes, and streams.

At other times of the year they stay in and under rotten logs or in moist places underground such as rodent burrows.

They are often found under surface objects near breeding pools or streams in the breeding season, and under driftwood on streambanks after storm waters recede. |

| Sound |

When molested, terrestrial Northwestern Salamanders may emit a ticking sound from their defensive stance.

According to Stebbins and Cohen, 1997, the Northwestern Salamander "produces a 'tic' sound, constant in character, when engaging in aggressive or defensive behavior. (Licht, 1973.) |

| Defense |

Adults and larvae are mildly poisonous which may explain their survival in lakes and streams with populations of introduced fishes and bullfrogs - not typical of many other ambystomatid salamanders.

When molested, terrestrial Northwestern Salamanders may emit a ticking sound and assume a defensive posture with the head down and the tail elevated while secreting a sticky white poison from parotoid glands on the head, back, and tail. Sometimes they will butt their head and lash their tail to smear the poison on an attacker.

This poison can kill or sicken small animals and causes skin irritation in some people. |

| Diet and Feeding |

Terrestrial individuals eat small invertebrates.

Neotenic adults consume aquatic invertebrates and tadpoles.

Hatchlings first consume tiny aquatic crustaceans, then, as they get larger, they consume larger prey including insect larvae, snails, worms, tadpoles, and fairy shrimp. |

| Reproduction |

Reproduction is aquatic, occurring in semi-permanent and permanent lakes, ponds, wetlands, and slow-flowing streams and rivers.

Salamanders most likely become sexually mature at 1 - 2 years of age.

Adults migrate to breeding waters and breed between January and April at low-elevation sites.

Breeding occurs from June to late as August at high elevation sites in the Cascades, and can take place when there is still ice on the ponds.

Peak breeding activity is known to be late February in the Seattle area.

Males arrive at the breeding site before females.

Breeding lasts from 1 - 7 weeks, the duration being dependent on the rate of temperature increase of the water.

|

| Eggs |

Metamorphosed females lay 30 - 270 eggs in masses that are roughly the size of a small grapefruit , and attach them to underwater shrub branches, grass, or aquatic plants.

Neotenic females lay eggs in masses that are smaller and looser and leave them directly on the bottom of the breeding pond or lake.

Eggs become invaded by algae, which provides them with oxygen.

Eggs hatch in 2 - 9 weeks. |

| Young |

Larvae are pond-adapted, brown or olive green in color, with dark pigment along the base of the dorsal fin, and long feathery gills.

Larvae usually overwinter and transform after 12 - 14 months at around 3.5 inches (85 cm.) in length.

Some larvae overwinter a second year, and at high elevations, they may overwinter a third year before transforming.

Some never transform, becoming neotenic adults.

|

| Habitat |

In California, found in moist habitats along the Pacific coast, including grasslands, woodlands, and forests.

|

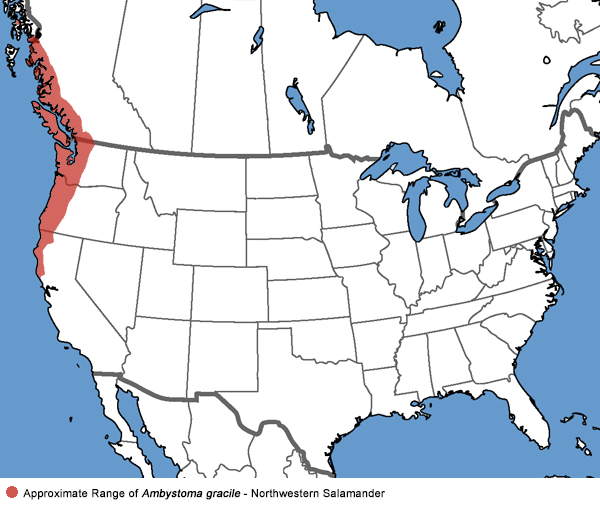

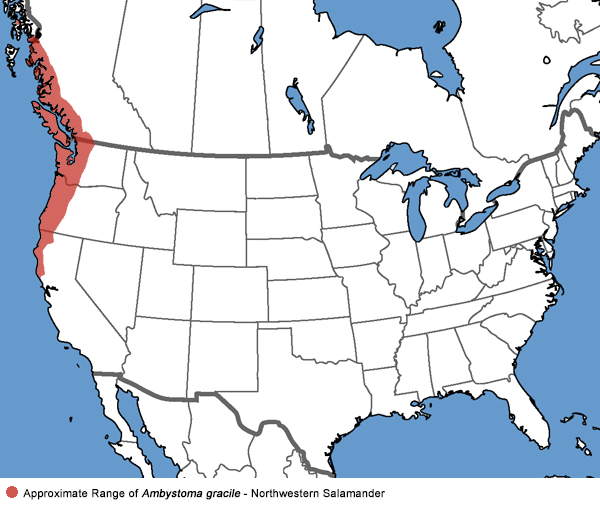

| Geographical Range |

Occurs from the central Sonoma County coast, north along the coast region and north Coast Ranges through the Cascade Mountains into British Columbia and north all the way to Chichagof, Alaska.

(Mark Gary, a contributor to this web site, found this salamander in central Sonoma county in 2005 near the Kruse Rhododendron Preserve. Previously, it was only recorded as far south as the mouth of the Gualala River.) |

|

| Elevational Range |

From sea level to near 5,700 ft. in the Cascade Mountains of Washington.

|

| Notes on Taxonomy |

Some experts have recognized two subspecies of Ambystoma gracile - A. g. decorticatum, a spotted form found in the range north of latitude 51 ° N. (which is about 1 ° north of Vancouver, B.C.) and A. g. gracile to the south.

Alternate and Previous Names (Synonyms)

Ambystoma gracile - Northwestern Salamander (Stebbins 2003

Ambystoma gracile gracile - Brown Salamander (Stebbins 1954, 1966, 1985)

Ambystoma gracile - Northwestern Salamander (Bishop 1943)

Ambystoma paroticum - British Columbia Salamander (Storer 1925)

Ambystoma paroticum - British Columbia Salamander - Vancouver's Salamander (Grinnell and Camp 1917)

Ambystoma paroticum (Baird 1867)

|

| Conservation Issues (Conservation Status) |

| This species remains common in much of their range, though they have lost suitable habitat through urbanization and agricultural development, and have undergone temporary declines in areas of clearcut logging. |

|

| Taxonomy |

| Family |

Ambystomatidae |

Mole Salamanders |

Gray, 1850 |

| Genus |

Ambystoma |

Mole Salamanders |

Tschudi, 1838 |

Species

|

gracile |

Northwestern Salamander |

(Baird, 1859) |

|

Original Description |

Baird, 1859 - Pacific R. R. Report, Vol. 10, Williamson's Route, Pt. 4, No. 4, p. 13, pl. 44, fig. 2

from Original Description Citations for the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Meaning of the Scientific Name |

Ambystoma - Greek - amblys = blunt + stoma = mouth

gracile - Latin = slender, delicate

[This species is fairly thick, but it has a slender tail, so maybe that's what gracile describes.]

from Scientific and Common Names of the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America - Explained © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Related or Similar California Salamanders |

Coastal Giant Salamander

Black Salamander

California Tiger Salamander

Southern Long-toed Salamander

|

|

More Information and References |

California Department of Fish and Wildlife

AmphibiaWeb

Hansen, Robert W. and Shedd, Jackson D. California Amphibians and Reptiles. (Princeton Field Guides.) Princeton University Press, 2025.

Stebbins, Robert C., and McGinnis, Samuel M. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Revised Edition (California Natural History Guides) University of California Press, 2012.

Stebbins, Robert C. California Amphibians and Reptiles. The University of California Press, 1972.

Flaxington, William C. Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Field Observations, Distribution, and Natural History. Fieldnotes Press, Anaheim, California, 2021.

Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025. Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with Comments Regarding Confidence in Our Understanding. Ninth Edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. [SSAR] 87pp.

Samuel M. McGinnis and Robert C. Stebbins. Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles & Amphibians. 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2018.

Stebbins, Robert C. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003.

Behler, John L., and F. Wayne King. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant, and Joseph T. Collins. Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Powell, Robert., Joseph T. Collins, and Errol D. Hooper Jr. A Key to Amphibians and Reptiles of the Continental United States and Canada. The University Press of Kansas, 1998.

American Museum of Natural History - Amphibian Species of the World 6.2

Bartlett, R. D. & Patricia P. Bartlett. Guide and Reference to the Amphibians of Western North America (North of Mexico) and Hawaii. University Press of Florida, 2009.

Bishop, Sherman C. Handbook of Salamanders. Cornell University Press, 1943.

Lannoo, Michael (Editor). Amphibian Declines: The Conservation Status of United States Species. University of California Press, June 2005.

Petranka, James W. Salamanders of the United States and Canada. Smithsonian Institution, 1998.

Corkran, Charlotte & Chris Thoms. Amphibians of Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia. Lone Pine Publishing, 1996.

Jones, Lawrence L. C. , William P. Leonard, Deanna H. Olson, editors. Amphibians of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle Audubon Society, 2005.

Leonard et. al. Amphibians of Washington and Oregon. Seattle Audubon Society, 1993.

Nussbaum, R. A., E. D. Brodie Jr., and R. M. Storm. Amphibians and Reptiles of the Pacific Northwest. Moscow, Idaho: University Press of Idaho, 1983.

Stebbins, Robert C. and Nathan W. Cohen. A Natural History of Amphibians. Princeton University Press, 1997.

Joseph Grinnell and Charles Lewis Camp. A Distributional List of the Amphibians and Reptiles of California. University of California Publications in Zoology Vol. 17, No. 10, pp. 127-208. July 11, 1917.

Boundy, J. and Balgooyen, T. G. (1988). "Record lengths of some amphibians and reptiles from the western United States." Herpetological Review, 19, 27.

|

|

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the July 2025 State of California Special Animals List and the July 2025 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists, but they don't change a great deal from year to year.. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists:

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals.

A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page.

If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings.

Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website.

This salamander is not included on the Special Animals List, meaning there are no significant conservation concerns for it in California according to the California Department of Fish and Game.

|

| Organization |

Status Listing |

Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking |

|

|

| NatureServe State Ranking |

|

|

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) |

None |

|

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) |

None |

|

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

None |

|

| Bureau of Land Management |

None |

|

| USDA Forest Service |

None |

|

| IUCN |

|

|

|

|

|